| Data Structures | Source Location | |

|---|---|---|

| |

Caution: the Architecture Guide is not updated in lockstep with the code base and is not necessarily correct or complete for any specific release.

Transactions provide a powerful abstraction for multiple threads to operate on data concurrently. A caller of WiredTiger uses Transactional applications within the API to start and stop transactions within a session (thread of control).

Internally, the current transaction state is represented by the WT_TXN structure.

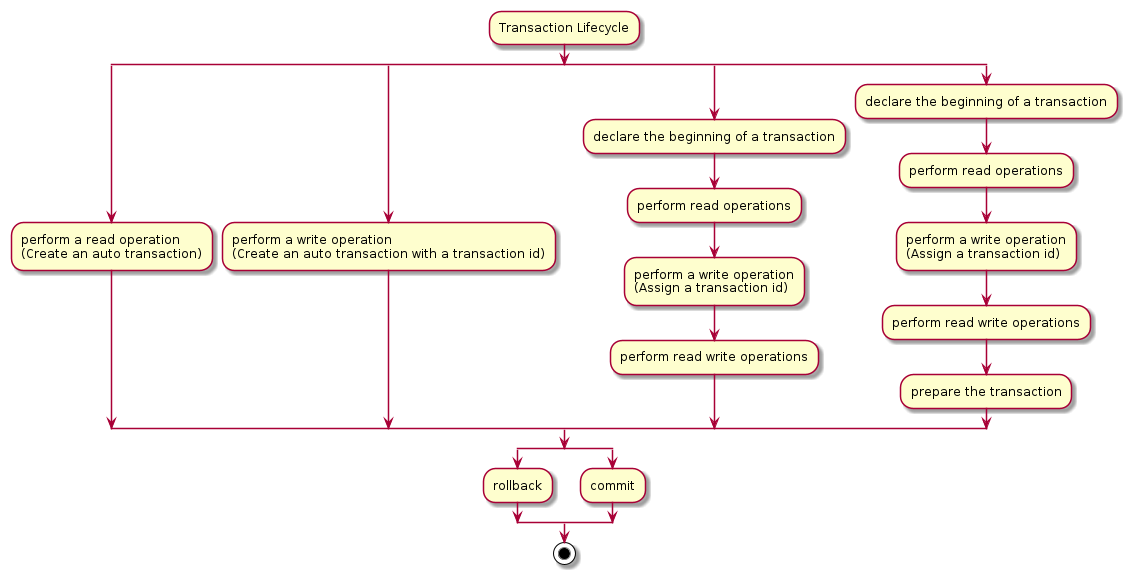

Except schema operations, WiredTiger performs all the read and write operations within a transaction. If the user doesn't explicitly begin a transaction, WiredTiger will automatically create a transaction for the user's operation.

A WiredTiger session creates and manages the transactions' lifecycle. One transaction can be run at a time per session, and that transaction must complete before another transaction can be started. Since every session is singly-threaded, all the operations in the transaction are executed on the same thread.

A transaction starts in two scenarios, when the user calls begin via WT_SESSION::begin_transaction or internally when the user performs either a read or write operation. Internally they are only started if they are not already within the context of a running transaction. If declared explicitly the transaction will be active until it is committed or rolled back. If it is created internally, it will cease to be active after the user operation either successfully completes or fails.

If the transaction is committed successfully, any write operation it performs is accepted by the database and will be durable to some extent based on the durability setting. Otherwise, all the write operations it has done will be reverted and will not be available any more.

Like other databases, transactions in WiredTiger enforce the ACID properties (atomicity, consistency, isolation, and durability).

All write operations initially happen in memory in WiredTiger and will not be written to disk until the entire transaction is committed. Therefore, the size of the transaction must fit in memory.

To rollback the transaction, WiredTiger only needs to mark all the write operations of that transaction as aborted in memory. To ensure no partial transaction is persisted to disk, the eviction threads and the checkpoint threads will do proper visibility checks to make sure each persisted operations are actually visible in regards to their snapshot.

There is one case that atomicity of transactions is not honored using timestamps in WiredTiger. If the operations in the same transaction are conducted at different timestamps and the checkpoint happens in between the timestamps, only the operations happen before or at the checkpoint timestamp will be persisted in the checkpoint and the operations happen after the checkpoint timestamp in the transaction will be discarded.

There is another case that atomicity may be violated if a transaction operates both on tables with logging enabled and disabled after restart. The operations on the tables with logging enabled will survive the restart, while the operations on the non-logged tables may be lost if it is not included in the latest checkpoint.

Isolation is one of the important features of a database, which is used to determine whether one transaction can read updates done by the other concurrent transactions. WiredTiger supports three isolation levels, read uncommitted, read committed, and snapshot. However, only snapshot is supported for write operations. By default, WiredTiger runs in snapshot isolation.

Each transaction in WiredTiger is given a globally unique transaction id before doing the first write operation and this id is written to each operation done by the same transaction. If the transaction is running under snapshot isolation or read committed isolation, it will obtain a transaction snapshot which includes a list of uncommitted concurrent transactions' ids at the appropriate time to check the visibility of updates. For snapshot transaction, it is at the beginning of the transaction and it will use the same snapshot across its whole life cycle. For read committed transaction, it will obtain a new snapshot every time it does a search before reading. Due to the overhead of obtaining snapshot, it uses the same snapshot for all the reads before calling another search. Read uncommitted transactions don't have a snapshot.

If the transaction has a snapshot, each read will check whether the update's transaction id is in its snapshot. The updates with transaction ids in the snapshot or larger than the largest transaction id in the snapshot are not visible to the reading transaction.

When operating in read committed or read uncommitted isolation levels, it is possible to read different values of the same key, seeing records not seen before, or finding records disappear in the same transaction. This is called a phantom read. Under snapshot isolation, WiredTiger guarantees repeated reads returning the same result except in one scenario using timestamps.

WiredTiger provides a mechanism to control when operations should be visible, called timestamps. Timestamps are user specified sequence numbers that are associated with each operation. In addition, users can assign an immutable read timestamp to a transaction at the beginning. A transaction can only see updates with timestamps smaller or equal to its read timestamp. Note that read timestamp 0 means no read timestamp and the transaction can see the updates regardless of timestamps. Also note that timestamps don't have to be derived from physical times. Users can use any 64 bit unsigned integer as logical timestamps. For a single operation, the timestamps associated with the operations in the same transaction don't have to be the same as long as they are monotonically increasing.

Apart from the operation level timestamps, the users are also responsible for managing the global level timestamps, i.e, the oldest timestamp, and the stable timestamp. The oldest timestamp is the timestamp that should be visible by all concurrent transactions. The stable timestamp is the minimum timestamp that a new operation can commit at.

Only transactions running in snapshot isolation can run with timestamps.

See Timestamps for further discussion.

The visibility of the transactions in WiredTiger considers both the operations' transaction ids and timestamps. The operation is visible only when both its transaction id and its timestamp are visible to the reading transaction.

To read a key, WiredTiger first traverses all the updates of that key still in memory until a visible update is found. The in-memory updates in WiredTiger are organized as a singly linked list with the newest update at the head, called the update chain. If no value is visible on the update chain, it checks the version on the disk image, which is the version that was chosen to be written to disk in the last reconciliation. If it is still invisible, WiredTiger will search the history store to check if there is a version visible to the reader there.

WiredTiger transactions support commit level durability and checkpoint level durability. An operation is commit level durable if Logging is enabled on the table. After it has been successfully committed, the operation is guaranteed to survive restart. An operation will only survive across restart under checkpoint durability if it is included in the last successful checkpoint.

WiredTiger introduces prepared transactions to meet the needs of implementing distributed transactions through two-phase commit. Prepared transactions only work under snapshot isolation.

Instead of just having the beginning, operating, and rollback or commit phase, it has a prepared phase before the rollback or commit phase. After prepare is called, WiredTiger releases the transaction's snapshot and prohibits any more read or write operations on the transaction.

By introducing the prepared stage, a two-phase distributed transaction algorithm can rely on the prepared state to reach consensus among all the nodes for committing.

Along with the prepared phase, WiredTiger introduces the prepared timestamp and durable timestamp. They are to prevent the slow prepared transactions blocking the movement of the global stable timestamp, which may cause excessive amounts of data to be pinned in memory. The stable timestamp is allowed to move beyond the prepared timestamp and at the commit time, the prepared transaction can then be committed after the current stable timestamp with a larger durable timestamp. The durable timestamp also marks the time the update is to be stable. If the stable timestamp is moved to or beyond the durable timestamp of an update, it will not be removed from a checkpoint by rollback to stable.

The visibility of the prepared transaction is also special when in the prepared state. Since in the prepared state, the transaction has released its snapshot, it should be visible to the transactions starting after that based on the normal visibility rule. However, the prepared transaction has not been committed and cannot be visible yet. In this situation, WiredTiger will return a WT_PREPARE_CONFLICT to indicate to the caller to retry later, or if configured WiredTiger will ignore the prepared update and read older updates.